Book Review: Nonviolent Communication

How to improve relationships and get what everyone wants

An algorithm is a defined process to follow to get a desired result. Much of our lives are decided by algorithms. Knowing what algorithms to follow can result in more efficient and effective decision making.

I recently re-read Algorithms to Live By, a book by Brian Christian and Tom Griffiths on how algorithms can help us be more effective in our lives. Having picked up programming last year, I got more out of this time around.

An algorithm is a process, and you can think of it as instructions to follow to complete some task. For example, learning how to add numbers together is a simple algorithm 1.

More complex instructions can calculate results for other problems in life. Interest rates, web search rankings, or social media feeds are all based on the output of algorithms. The book goes through many such algorithms, and relates them to problems you might face personally.

It’s too difficult to explain every algorithm they mention 2, so instead I’ll be doing short highlights from some, and usually concentrating on the qualitative, not quantitative takeaways.

Also, most of the algorithms rely on certain assumptions; rather than specify that every time, take that as a given when reading. I’ll add some of the assumptions in footnotes for those interested.

Some of the problems discussed include:

Let’s look at our first algorithm, on when you should stop working on a problem.

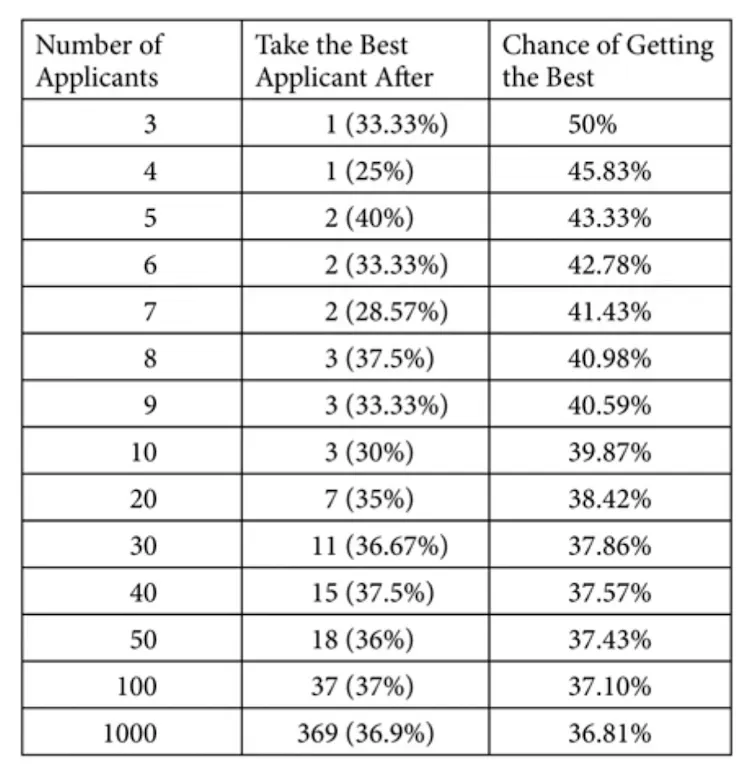

If you’re evaluating options (job applicants, housing offers, parking spaces etc), there’s a tradeoff between how long you spend choosing, and the chance of picking the “best” option. This is known as the secretary problem - suppose you were hiring a secretary, how many interviews should you do to get the best chance of finding the best one?

In this case, there’s a precise percentage to use. You should wait after seeing 37% of the applicant pool, and then take the next best applicant you see 3. For example, if you had 100 applicants, wait after you’ve seen the first 37, and then pick the next applicant that is better than all you’ve seen so far.

That is the mathematically optimal point with the highest chance of picking the best person for the job. If you stop too early, you might miss someone interviewing later. If you stop too late, you waste time 4.

Similar to the optimal stopping situation, there’s a tradeoff between information gathering (explore) and enjoying (exploit). Suppose you’re at a casino, and want to decide which machines to play. You want to maximise your winnings, but don’t know the exact odds for the machines (if you did, you’d play the best one).

In this case, there’s a number, known as the Gittins Index, that gives you the optimal machine to play 5. If you know the number of wins, losses, and how much you value future gains, you can calculate precise values for each choice. Some interesting properties:

Some other related implications:

The book gave a few examples of sorting algorithms, which are commonly used in programming. For example, returning search results requires a sorting of the most relevant ones for you.

I’ll save more detailed discussion of sorting algos for another day since they require understanding time complexity. Here are some qualitative takeaways:

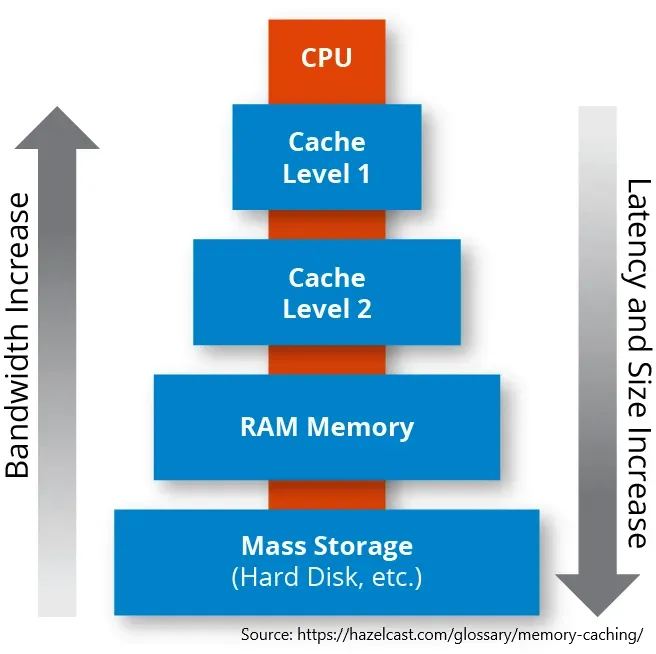

The idea of having a cache is to have 1) a small, fast memory (storage) section, and 2) a large, slow memory section. We’ll then alternate between the two depending on what our intention is. This lets us get both some amount of speed and some amount of size for the activity we want.

For example, you might have your favourite clothes in your wardrobe, and your unused ones in the attic. You’d have quick access to the items you used the most, but still have space for that ugly christmas sweater if you wanted. Caching sounds complicated, but you’ll realised we do it naturally for most of our daily lives.

How do you decide what items should be put in the fast section, and what items in the slow section? You could put random items, the newest item, the largest item etc.

In this case, keeping the most recently used items in the small and fast section is the optimal choice, due to something known as temporal locality. You’re more likely to need something again that’s something you’ve recently used. For example, google drive highlights your frequently used files for quick access.

Most of us have to decide how to prioritise items on our to do list. This usually requires making a tradeoff between responsiveness (how quickly you respond) and throughput (how much you can get done).

A key point about scheduling and prioritisation is defining your goal metric, since that determines what algorithm you want to use 7. Maximising responsiveness comes at the expense of how much you can get done:

If you want to minimise the max lateness of all your projects 8, the Earliest Due Date algorithm tells you to start with the project due earliest.

If you want to minimise the total completion time, the Shortest Processing Time algorithm tells you to just do the quickest task first.

If your tasks are not equal in importance, then placing a weight on each task and calculating the weight over time required ratio will help you decide which task to do; pick the project with highest weight over time.

Practically, this means that it’s probably worth having a conversation with your manager on how the team thinks about this tradeoff, and which method they’d prefer you adopt.

There’s another important concept in scheduling, which is the idea of context switching - whenever you have to switch between tasks. Context switching is wasted time since it’s not real work, but takes up time and effort on your part.

For example, if you were writing an email and then got interrupted by a slack message, it takes time for you to both respond to the slack message, and then remember what you wanted to do for the email.

At its worst, context switching turns to thrash, when you get nothing productive done because you’re too busy with only switching. Ways to avoid thrash include:

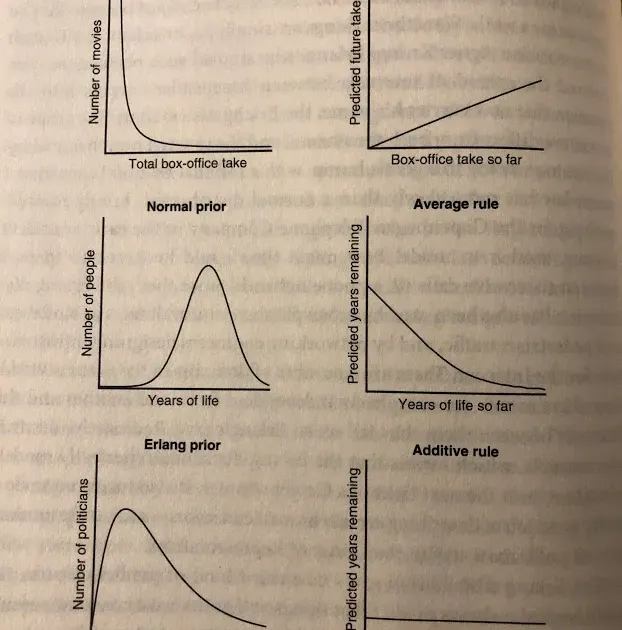

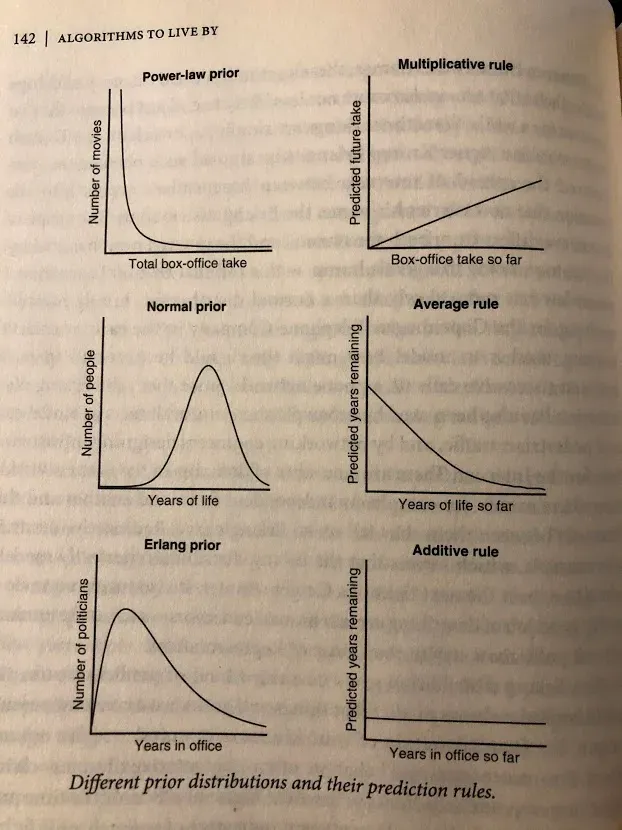

Explaining Bayes rule would probably take an article on its own, so let’s just take it as a rule that helps you with predicting how likely something is to occur 9. What the authors want to highlight is that this depends on the distribution that your events are coming from. There are three main distributions to think about:

Most of us have probably heard of game theory before, which is a way of thinking what the optimal strategy is when playing a game. Some highlights:

Besides the algorithms mentioned above, the authors also go through:

Overall I thought the book was worth reading to get an overview of interesting ways algorithms show up in life. I did understand it better after learning some computer science though, so keep that in mind. I also wish that they’d included more practical examples 10, since trying to apply the findings to life can be difficult when you have to work off different assumptions.

Easy enough to teach children, by telling them to memorise sums and when to carry a number, but surprisingly not obvious when trying to implement on a computer, see full adder logic gate ↩

You might say that by the time I explain everything, I might as well have written the entire book ↩

The percentage is 1 divided by e, euler’s number. The chance doesn’t change as the size of the applicant pool grows, but does change with different information states you get ↩

The base secretary problem assumes that you can’t go back to a candidate that you passed on, but there are variations that resemble real life a bit more closely. ↩

This problem is intractable if the probabilities of a payoff on a machine change over time; essentially meaning it’s unsolvable. Some problems are intractable. In these cases, relaxing some constraints and accepting solutions that are “close enough” helps us significantly in structuring the problem. ↩

Or March Madness, for the Americans ↩

Only 9% of all scheduling problems can be solved efficiently. ↩

As in, take all your projects that are late, and then the maximum of those. That’s the metric you want to minimise. ↩

See here for an article that explains Bayes. Bayes is unintuitive (for me at least), which also means its good to know ↩

To be fair, there’s a good amount of information in the footnotes elaborating more ↩

Get my next essays in your inbox:

Comments