What is art

Different definitions of art over history

A research paper proposes that you should look to work with strong teammates and not strong companies if you’re interested in innovation

We discussed middlemen in financial capital last week. This week, let’s look at middlemen in human capital.

In the paper “Are Inventors or Firms the Engines of Innovation?” Ajay Bhaskarabhatla, Luis Cabral, Deepak Hegde, and Thomas Peeters look into whether we should credit humans or companies more for innovations. Surprisingly, they find that humans deserve much more merit. Let’s take a closer look.

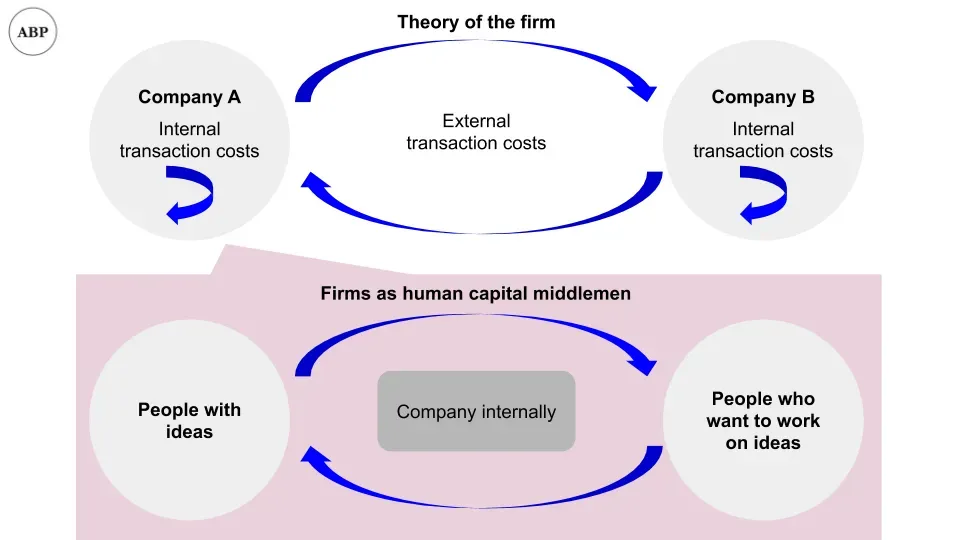

We can think about companies as performing a middleman role of “matching people together,” bringing together people with ideas and people who want to execute. There’s a whole Theory of the Firm on how companies exist to reduce transaction costs [^1]. Under this framework, we could try and split out the effect of innovation between the people and the firm.

Whether firms or humans deserve more credit can help us know where to focus on if we want to get more innovation:

Indeed, if the ability to invent rests with firm-specific structure, culture, and routines that are hard to transfer across organizational boundaries, then inventors may be substitutable, and firms should develop capabilities that enhance innovation. If, on the other hand, human capital is critical for innovation, then firms’ innovativeness will depend on their ability to screen, attract and retain talented workers.

To study this, the researchers first define inventor patent count as the measure of innovation. The more patents someone creates, the more innovative [^2].

They then look at a subset of companies which had inventors move among companies within that set. Intuitively, an inventor moving from one company to another allows you to measure the effect of the person vs the firm, pre and post-move. This restriction gave them 709,000 inventors at 2,500 U.S. publicly listed firms to analyse [^3].

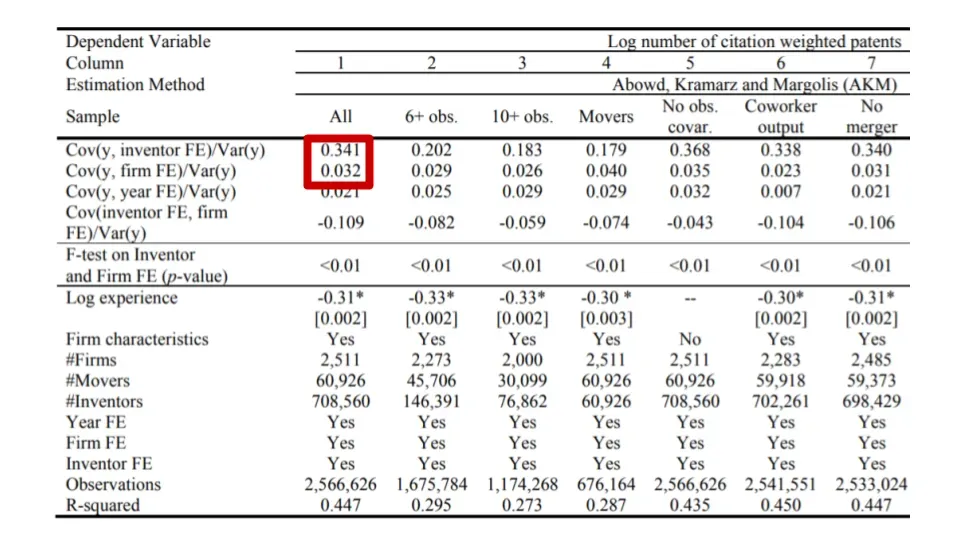

Using that data, they run a regression to see if patent count can be predicted from inventor related causes, firm related causes, or other variables. They find that while both inventor and firm are statistically significant explainers of patent count, the importance of inventors is nearly 10x larger than that of the firm:

inventor-specific fixed effects explain 18-37 percent of the observed variance in inventors’ patenting performance. In contrast, only 2-7 percent of the overall variance in inventor productivity is explained by firm fixed effects. The observed firm-level variables, such as age, size, patent stock and R&D intensity, explain another 1 to 8 percent of the overall variance. These results suggest inventor-specific human capital explains much of the variance in inventor output

The table below has a lot of numbers, and let’s ignore all of them except the two in the red box. That comparison of the 0.341 for inventors vs 0.032 for firms is what the researchers are referring to in the above quote; higher numbers mean more explanatory power for patent count. For our purposes, just think of fixed effects as meaning “effect”, but you can read more about the actual definition here.

If the above is true, then that means that as individuals, we should look to work with strong teammates, rather than strong firms if we’re interested in being more innovative. Put another way, it’s a data point towards why you should care a lot about the people you’re going to directly work with, rather than the reputation of the company.

Another counterintuitive result the researchers find is that “good” companies don’t necessarily have more “good” inventors:

low human capital inventors match with high innovation capability firms. The idea is that the innovation boost provided by firms with high innovation capabilities is particularly valuable for low human capital inventors, who are willing to accept lower wages for the “amenity” of higher innovation rates.

By contrast, high human capital inventors cluster at firms with low innovation capabilities. Intuitively, these inventors have less to gain from their employer’s innovation capabilities, placing a relatively greater weight on their financial compensation

The above is saying that if you believe yourself to not be as innovative, you’ll go work at a company more known for innovation, to try and get some benefit for yourself. As a tradeoff, you’re willing to accept lower salaries.

If you think you’re more innovative, you’ll care less about the company, and prefer a higher salary since you don’t need the firm’s innovation benefit [^4].

This result is harder for me to accept and understand. The paper does claim to have controlled for firm size and stage [^5], and I still wonder if there’s some startup company effect here. If startups have less patent output as new firms, and are more selective with hiring, you might see the case of high human capital joining low innovation firms, and negotiating for higher financial compensation once equity is included. I don’t know enough to dig further into their methodology, but could be something to consider.

The researchers also include an entire page of other limitations with the study. The big ones include using patent count as the definition of innovation and assuming that wages and potential innovation output are being traded off. You can read more in the footnote or in page 23 of the paper [^6].

Assuming you believe in their research though, the main takeaways are:

Get my next essays in your inbox:

Comments