Ergodicity: What Does It Mean?

Why the difference between ensemble and time averages matters for investing and risk

Third Point argues that Disney should stop paying its dividend and invest in streaming; Semper Augustus disagrees.

The activist investment fund Third Point recently published a letter to Disney, suggesting the company change their business strategy 1. This led to a rebuttal by another investment firm, Semper Augustus (h/t Joe Koster). It’s less common for investment firms to provide counterarguments against an activist, so let’s take a look at both sides 2.

To set the stage, let’s briefly go over activism and Disney’s business, for those unaware of either.

Activist funds like Third Point usually take a small stake in a company, before publicly agitating for company management to take actions which the activists believe will increase company value. These actions could include paying a dividend, selling off bad business units, or replacing company management. Company value here typically defined as an increase in the stock price. Activism has risen in popularity the past decade; back when I was in banking I even worked on defending a company against an activist proxy fight (which went horribly, but that’s a separate story).

Famous funds and investors include Carl Icahn, Bill Ackman’s Pershing Square, and David Einhorn’s Greenlight Capital. Since activists want to be listened to, they’re usually higher profile than other hedge funds. It helps them when they get press and they’re incentivised to be publicity seeking.

Success for an activist investor looks like this: buy stock in a company, tell the company what to do, company does it, stock price goes up, everyone’s happy, activist sells stock and takes profit. Most activists are short term holders, though there are exceptions.

Failure could be any part of that step failing. For example, a company might not listen to you. And even if they did, maybe the stock price doesn’t move.

Now that we have a rough understanding of activism, let’s look at Disney.

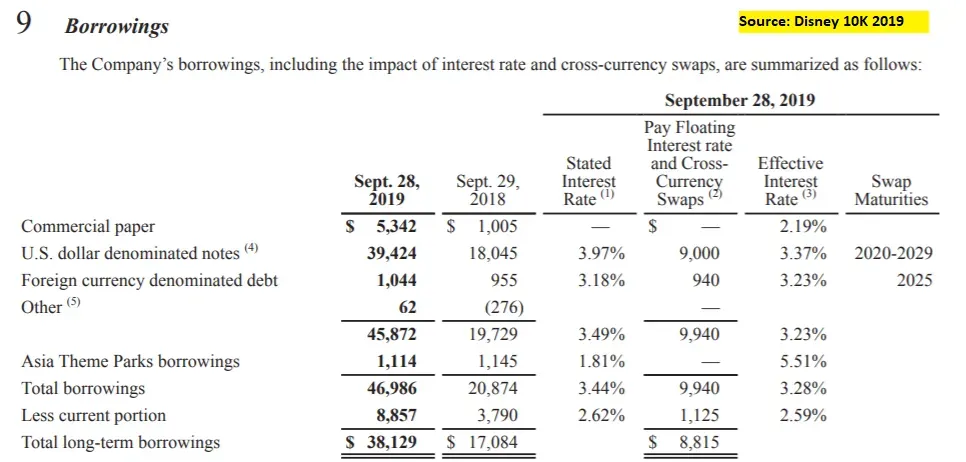

I never covered Disney when I was in long/short investing; a colleague did. Hence, let’s take a look at the financials and learn together how the business is run. I’ll be looking at their 2019 annual report for simplicity, so all the covid impact isn’t included yet. We’ll come back to that.

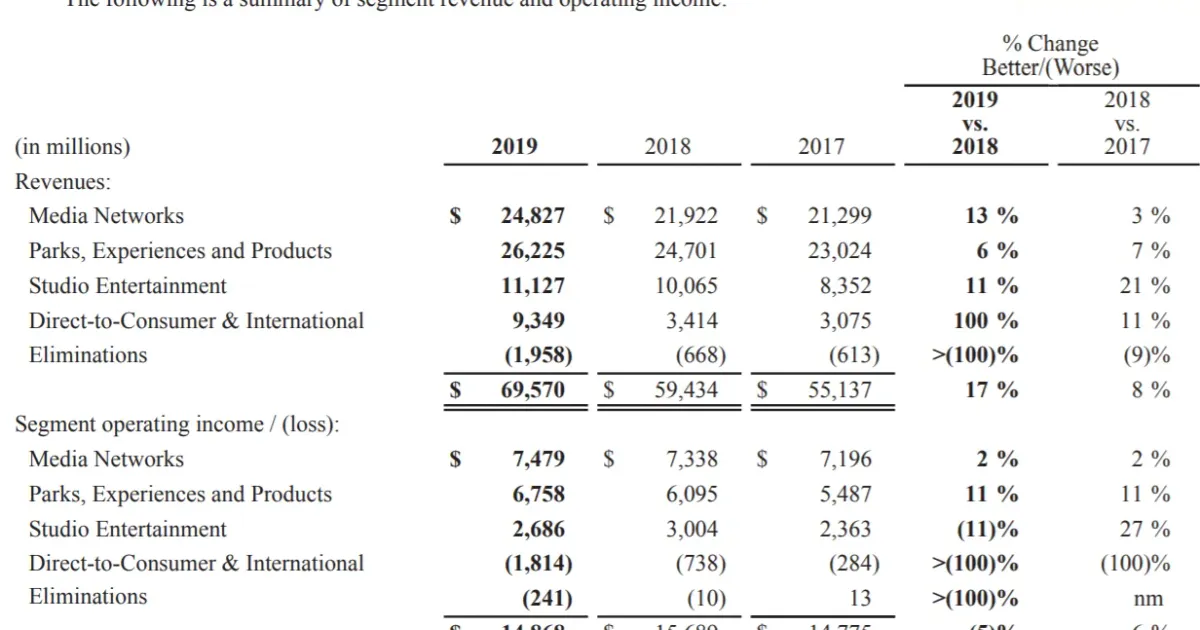

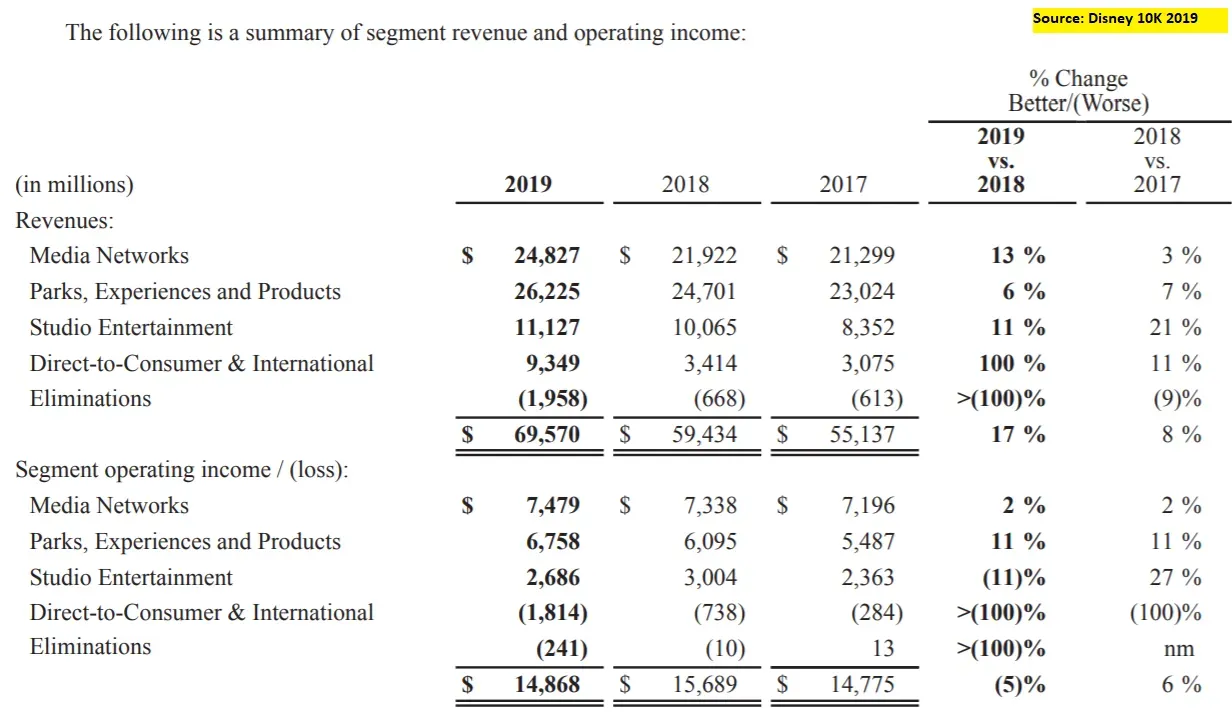

Disney reports four major segments, Media Networks, Parks, Studio Entertainment, and Direct-to-Consumer (DTC)

My first thoughts on the above are:

If we take a look at the operating margins of those segments, they’re pretty similar at 20-30%. That was surprising to me, I’d have thought there would be a high margin segment “subsidising” a low margin one e.g. my first guess would have been that Parks are low margin.

If the margin profiles are indeed similar, management should be indifferent to investing in any of them; perhaps preferring Media due to the slightly higher margin 4.

Disney takes 17 pages in its annual report to describe its business 5, so I’ll summarise them to avoid all of you bouncing before we even get started.

Reading over this section also answers a few questions I had:

There was an acquisition in 2019, which resulted in “extra” rev for both the Media and DTC segments. This explains why DTC growth was so high, and also the acceleration in the Media rev. Now I remember that Disney bought 21st Century Fox.

If this was me back in banking I’d have spent hours trying to do pro-forma financials to adjust for this and get a “normalised” growth, seeing both businesses separately.

I’m not in banking anymore and can’t be bothered will leave it as an exercise for the reader, so let’s move on. But that also implies the growth rate of Media is lower than I thought. I wouldn’t be surprised if it was more similar to the 2018 growth rate of ~3%.

I’d also initially thought DTC was showing Disney+ success, but that’s not the case. I also realised Disney+ launched in Nov, so it’s not contributing to revenue, as Disney’s fiscal year ends in September.

Parks are also higher margin than I thought because they lump the IP licensing rev in that segment. I’m assuming that’s to avoid showing a low margin segment, which is typical behaviour for many businesses, but don’t have context here.

So my revised thoughts are:

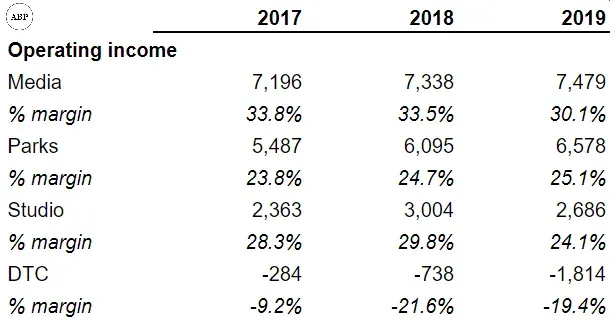

One enormous complication is Covid’s impact on the business. For the first nine months of its fiscal year:

I’ve put Disney’s financials into a simple model here in case any of you want to play around with the numbers. Note that the assumptions are just dummy numbers and not diligenced.

Now let’s take a look at what the investors are saying.

My original plan was to present the arguments and counterarguments for both investors. Turns out, there’s actually only one main point 7, so let’s get directly into it, skipping the usual opening spiels from both firms on how their firm and Disney are all so awesome.

we believe the company should permanently suspend its $3 billion annual dividend and redirect this capital entirely into content production and acquisition for The Walt Disney Company’s DTC businesses, centered around Disney+.

I googled it, and realised Disney suspended their dividend due to Covid. Third Point’s suggestion is interesting, since they’re saying they want Disney to give shareholders (such as themselves) less money, and re-invest it into the fast-growing DTC segment we saw earlier. Normally you’d see activists argue the opposite.

Third Point elaborates:

These incremental dollars would, based on our analysis, generate returns that are multiples of the stock’s current dividend yield by driving high life-time-value (“LTV”) subscribers to your DTC platform.

They’re arguing that the full value of a streaming subscriber is high, and so Disney should invest more on content to get more subscribers i.e. a dollar returned to an investor as a dividend is worth less than if Disney used that dollar to make content and get more subs

Beyond bringing additional subscribers onto the platform, increased velocity of dedicated content production will deliver several knock-on benefits spread across your existing base including elevated engagement, lower churn, and increased pricing power. To put this in perspective, improving Disney+ churn to Netflix’s industry-leading ~2% domestic churn levels would more than double gross subscriber LTV.

Common tactic of comparing a company to a “best in class” example, saying that if the company can perform as well as the example, dreams come true. In this case, they’re saying that more subs will stay subscribed, watch more shows, and Disney would be able to charge them more.

Of equal importance, meaningfully accelerating DTC content spend will further broaden the divide between The Walt Disney Company and its traditional media peers - AT&T’s WarnerMedia, Discovery, ViacomCBS, Comcast’s NBCUniversal and Fox – none of which have the financial capabilities to execute such a bold plan

I don’t have enough context here, since I don’t know how much those peers are spending. It is surprising to me that none of them would have enough cash to spend on programming though.

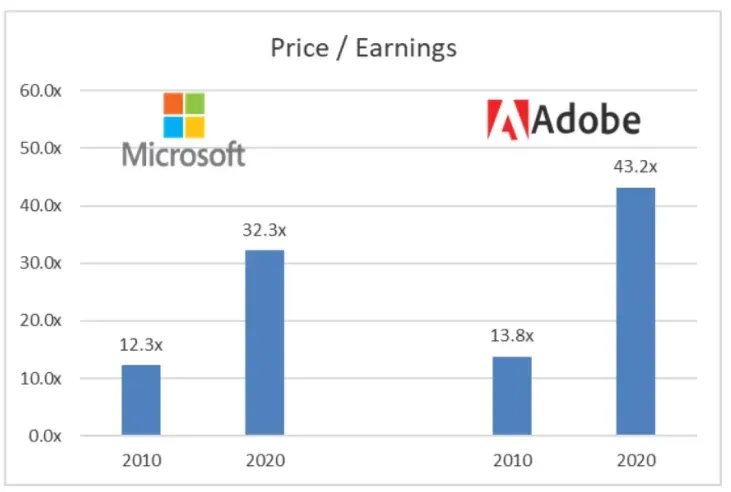

we have observed numerous precedents of successful non-linear business model transitions that paid off handsomely for shareholders. Among such business transformations, Adobe and Microsoft stand out as particularly relevant examples […] Furthermore, the stocks were rewarded with significantly higher multiples reflecting the superior quality of their new recurring, subscription revenue streams

And they include a graph showing the multiple increase. A multiple is one way of valuing a company, showing how much people are willing to pay for your stock. Higher is generally better 8.

Finally, we believe Disney should maintain its focus on transitioning to a subscription-led DTC revenue stream and avoid the temptation of maximizing short-term profits through transactional VOD pricing strategies.

Also interesting that they’re not asking Disney to aggressively monetise (getting consumers to pay for each film 9), and instead make the subscription as value for money as possible.

My first thought is this is an unusual, interesting activist ask. Rather than wanting shorter term return by asking for more dividends, Third Point is requesting the opposite. They don’t even want the company to push monetisation and seem to prefer waiting for a longer term pivot in the business model.

Now what does Semper have to say:

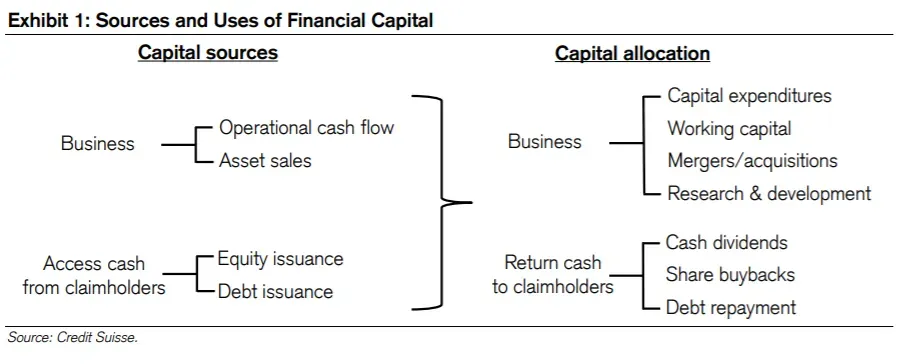

I challenge, however, the recommendation of, “permanently suspending Disney’s $3 billion annual dividend and redirecting the capital entirely into content production and acquisition of Disney’s DTC businesses, centered around Disney+.” This letter will not, however, suggest you reintroduce the dividend at the prior rate either, but rather to use this time as an opportunity to evaluate all capital allocation arrows available in your quiver.

So they’re saying to not accept Third Point’s suggestion right away, but to look at all alternatives. What might those be?

Retiring a portion of the now cumbersome debt taken on to finance the Twenty First Century Fox acquisition

Make any bolt-on acquisitions

Repurchase shares of common stock in the open market

Increase content, capital, research & development or advertising spending at the parks or in the studio and media businesses.

These are pretty standard capital allocation options. In fact, the first three are things I’d normally expect an activist to ask for, and before reading Third Point’s letter I was guessing they were going to say something like that. Here’s a quick image to refresh your memory about capital allocation, from Michael Mauboussin:

Back to Semper:

It seems the entertainment industry is in a nuclear arms race with an understanding that he who produces the most content wins. That doesn’t strike me as the Disney way.

Semper prefers Disney focus on quality not quantity.

Yes, if subscriber counts grow faster than expectations in the short term, the stock price is likely to be rewarded, in the short term. On a sufficient pop in the stock, we’d bet Third Point and that ilk of short-term speculator, defining success as an expansion in the price-to-earnings multiple, will be through the exit door.

This is a common critique of activists - that they’re only short term holders. I’m generally inclined to agree that activists on average are shorter-term, although I have seen counterevidence 10.

With the enormous caveat that I don’t cover Disney and never have, I’m leaning towards Third Point here. Which is surprising, since I normally find most activist arguments weak. Couple of reasons:

Again, caveat that this is not investment advice and that I’m less familiar with the sector, but that’s my current opinion. As mentioned, you’re welcome to make a copy of the financial model I put together here to play with the numbers. The assumptions I put in there are dummy numbers so please don’t anchor on them 11.

Feel free to reply letting me know what you think!

I’ve linked to a third party site for the letter text, and you can also find it here on Third Point’s official site if interested. That link doesn’t seem to be a permanent one for the letter, hence the third party link. ↩

But not unheard of. Bill Ackman vs Carl Icahn on Herbalife is a famous example. ↩

The 100% in the table stands for >100% growth, similar to the >(100)% standing for more than 100% decline ↩

This is a simplistic take, since there could be other costs not accounted for in the operating income reported here. The tax treatment for the businesses or interest expense might be different, just to give examples. ↩

It’s the first section of its annual report, if you’re interested in taking a closer look ↩

I think people know that ESPN is the big money maker for Disney from some other publicly disclosed numbers, but I’m not going to dig further unless needed. ↩

Third Point’s main argument starts in the third paragraph, and I’m unsure if this was intentional for Third Point. ↩

Again, simplistic take. If I wanted to dig further, I’d go check the multiples shown for those companies, how they’re calculated, and how they’ve trended over time. No doubt MSFT and ADBE have done well with their pivot and been rewarded for it. At the same time, 2010 seems to be soon after the 09 crisis, so multiples were probably depressed. Multiples in 2020 are probably also higher than normal. So some of the multiple expansion was from the business model transition, some of it was due to comparing a high point vs a low bar. ↩

Disney tried this with Mulan and googling shows people think it didn’t go well. ↩

Usually presented by the activists themselves, who will show some table of “Oh I’ve held so and so stock for 10 years” and then the stock turns out to be Amazon or something that everybody would want be a long term holder of. To be clear, I’m not saying activists can’t be long term holders, just that the business model by nature incentivises short term action. ↩

To be clear, if I were to actually model Disney, we would have to go into a lot more detail, such as estimating subscriber numbers and building each business segment bottoms up. The model’s a simplified one with dummy assumptions; the intent is to let people have a quick overview of the business and drivers ↩

Get my next essays in your inbox:

Comments