Ergodicity: What Does It Mean?

Why the difference between ensemble and time averages matters for investing and risk

Investment banking is rarely about investing, and more about connecting sources and users of financial capital.

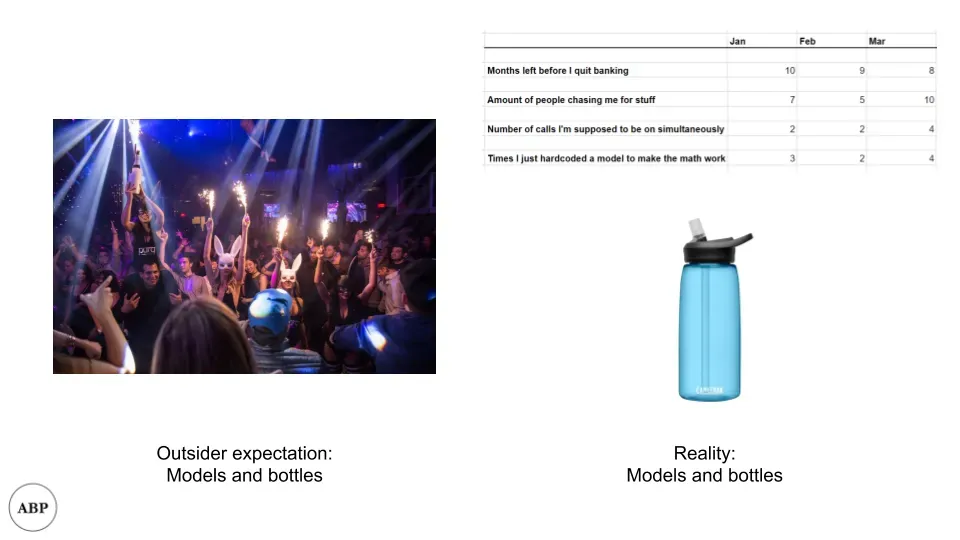

I’ve had to explain to a few people what investment banking’s actually about recently, and I figured I might as well do a short primer here as well. Especially given the mismatch between expectations and reality, hopefully this will help clarify things.

Investment banking is generally not about investing, despite my parents’ never seeming to have understood that. Sidenote: I’ve been trying to find the etymology of when “merchant banking” turned into “investment banking,” but haven’t had luck so far. If you happen to know, please get in touch.

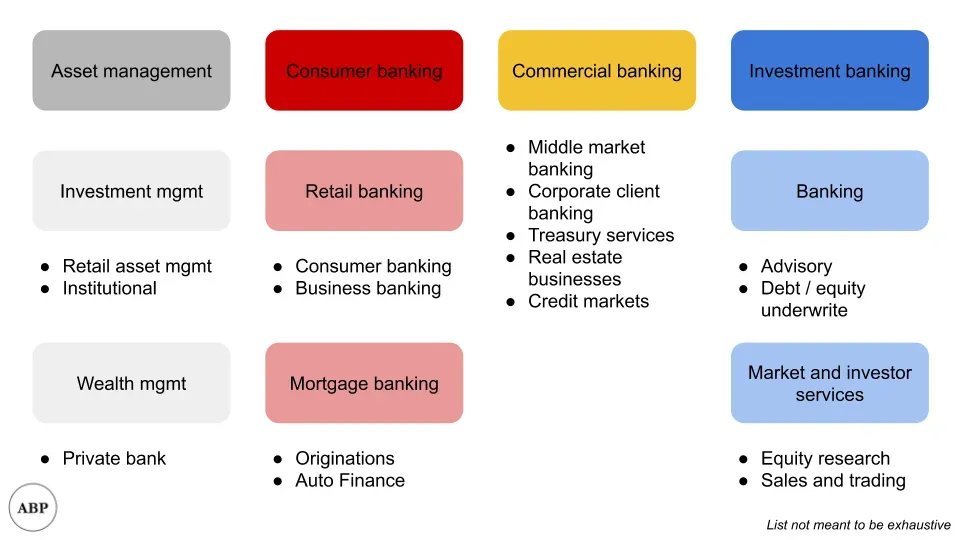

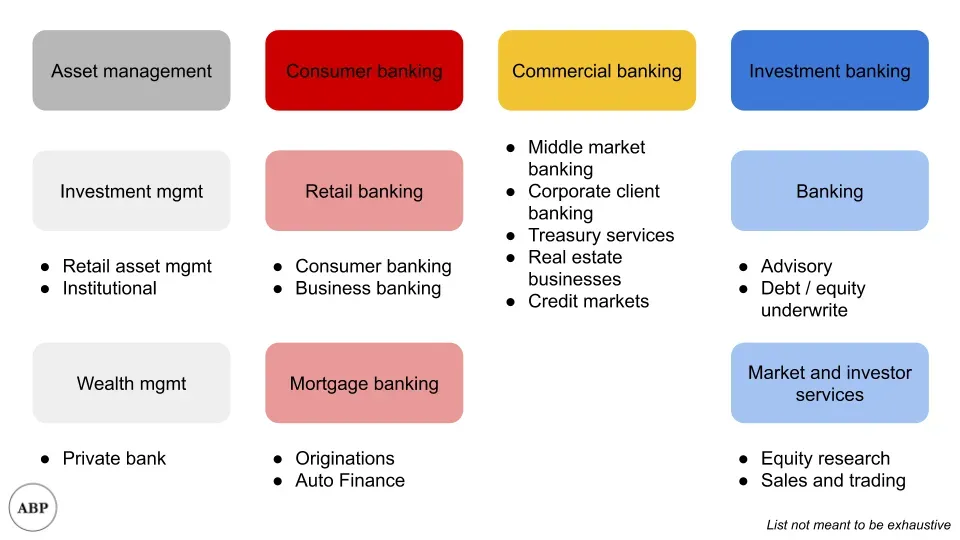

A “full service” bank like JP Morgan is enormous. You can think about it as four main lines of business:

When I refer to investment banking or banking in this article, I’m specifically talking about the blue business on the right. And to make my life easier, I’ll focus just on the “Banker” box, excluding discussion of the equity research and sales and trading arms for simplicity. I’ve mentioned equity research here before when discussing the impact of roboadvisors.

So now that we know our scope, what does the investment banking group do?

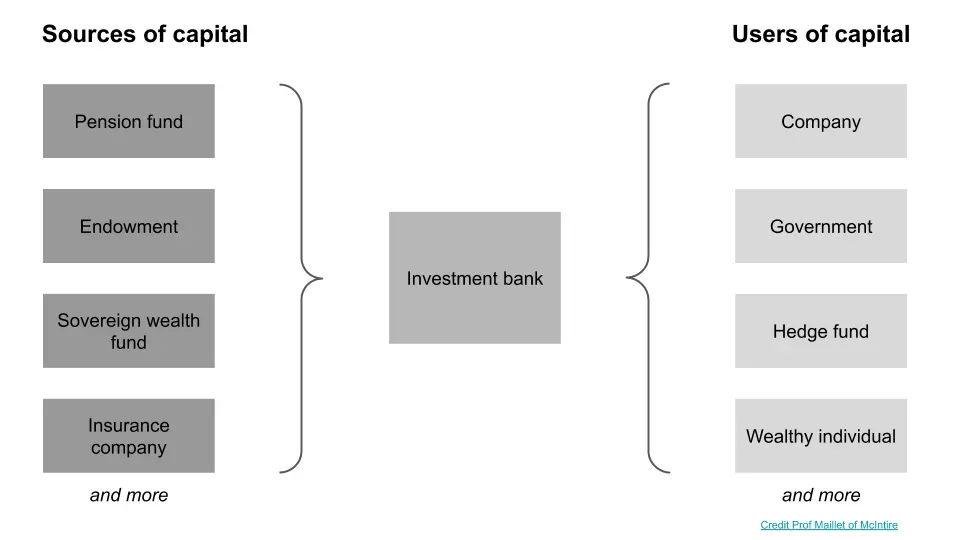

I’ve always liked this framework that a professor of mine used 1, and it goes like this:

Banks are middlemen. Specifically, middlemen of financial capital 2.

The world has a lot of people with capital, looking to use it. For example, a pension fund might be looking to diversify, an endowment might be wanting higher returns, or a company might be looking to acquire another.

The world also has a lot of people who need capital. For example, a company might issue debt or equity in order to fund their operations.

The business of the bank is to make a market between the two groups.

For example, if Google is trying to raise debt, the bank will work with it to figure out how much they can raise, who will buy the debt, and what terms the debt will be issued at.

Some but not all banks are structured into two large groups, industry coverage and product coverage 3. Industry referring to providing advice to companies in that industry vertical. Product here referring to a type of financial product such as corporate finance advisory, equity capital markets, debt capital markets, leveraged finance, and mergers and acquisitions.

Industry coverage is easier to understand, so I’ll just explain the various financial products.

Equity capital markets deals with most equity related products, from private placements (when a company wants to issue stock privately) to IPOs (when a company issues stock publicly). For example, if you’re going to IPO, part of the banking team you’ll work with will include ECM bankers. They’ll be working with sales to talk to investors and gauge demand for your stock.

Debt capital markets usually deals with investment grade debt products. If you don’t know what “grade” refers to, we’ll come back to that in a minute. For example, if you’re a company looking to issue debt for an acquisition, you’ll be working with a DCM team to understand what interest rates etc you’ll be able to get, based on investor demand.

Leveraged finance usually deals with non-investment grade debt. Historically, LevFin was considered more risky and exotic, until Michael Milken kickstarted the sector with the use of “risky” debt in private equity leveraged buyouts. That’s why there’s a different team for it, as the types of investors could be different and desiring different types of terms. For example, a company issuing non-investment grade instead of investment grade debt might have to accept higher interest rates, in exchange for weaker debt covenants.

Mergers and acquisitions deals with whenever companies want to buy or sell each other. For example, if you were looking to buy a smaller competitor, you’d work with an M&A banking team to get a valuation and discuss bidding strategy.

Corporate finance advisory is a team that provides financial advice, and often is used for debt ratings or activism advisory. The CFA team tries to model what the ratings agencies will rate your debt at. Coming back to “grade,” all public debt issuers have a “rating” associated with them and the debt they issue. There’s a few credit rating agencies such as S&P, Moody’s etc that will evaluate the terms and then give the debt a “rating,” which is supposed to represent how risky the debt is. For example, Google issuing debt would get a “low risk” grade, whereas a startup issuing debt would get a “high risk” grade.

To give a hypothetical example touching on all of the groups above, suppose you were a large company looking to acquire another large company.

You’d work with the industry coverage team for non-product specific work, such as industry related slides to justify the deal. The M&A team would help you build a financial model to assess bidding prices and pro forma merger financials.

Since it’s a large deal, you want to raise the cash from all available sources, so you’ll use investment grade debt, non-investment grade debt, and why not a private placement while you’re at it. This loops in the DCM, LevFin, and ECM teams. Since you’re doing debt stuff, it’ll also loop in the CFA team to estimate the ratings.

When the deal closes, the bank will take a percentage of the total deal size. The percentages vary depending on product, but as you can imagine that incentivises bankers to do larger deals.

Also note that most of banking money is made when an actual deal happens, so bankers are incentivised to make deals happen.

So, now that we know what banking is, do bankers actually add value?

It’s become more popular to hate on bankers the past decade, with the average person thinking bankers spend most of their time midget tossing and the average company executive thinking bankers don’t know their industry as well as the company does.

As with all things, it depends. Everyone hates middlemen until they have to try making a market for themselves.

It’s easy to say that a “well known” company like Palantir could IPO without much help from a bank, or that Google could issue debt directly. Large companies typically have entire finance teams of ex-bankers, so it’s not like they lack the knowledge. They’re in contact with investors regularly too, particularly if they’re a public company and have to do investor meetings. And they should hopefully know their industry space and competitors better than bankers do 4.

It’s harder for “lesser known” companies to do so. If you aren’t as large a company and don’t have a dedicated team, you’d want to outsource as much of this work as possible. For example, if you’re going to IPO and don’t even know where to begin and who to reach out to, working with a bank makes more sense. Or if you want to sell your company but not publicly announce that you’re for sale, bankers can be helpful too.

Additionally, there’s always the “cover my ass” factor, where bankers form a supposedly unbiased third party opinion on the acquisition. If the bank has valued the company at $10, there’s less chance of getting sued by someone saying you overpaid by offering $10.

There’s a popular narrative of bankers being disintermediated by tech or the latest financial innovation. While I agree that bankers do need to keep up and continue finding better ways to add value, I don’t see investment banks disappearing any time soon. If I had to make a prediction, I’d say with 90% certainty that the “investment bank” role is still around in 20 years, with its essential service still being a financial middleman, even if the companies change. Cynically, even if all of debt and equity issuances take place on some sort of tech platform, companies still need someone to blame when things go wrong.

Sometimes human capital too, but that’s usually unintentional and rarer ↩

I can’t actually remember anymore which ones have which structure. The alternative is to have a single group of industry coverage that does both functions. ↩

Banks do cover competitors, but there’s usually some form of “conflicts” process to try and prevent a banker covering two competitors at the same time, particularly for actual deals ↩

Get my next essays in your inbox:

Comments