Community as a Concept

CAC to lower your CAC

Michael Filler and Matthew Realff propose that all processes come from 8 different types of steps. By understanding what steps are available, you can rearrange them to get process improvement. Process improvement is underrated because of its intangible nature.

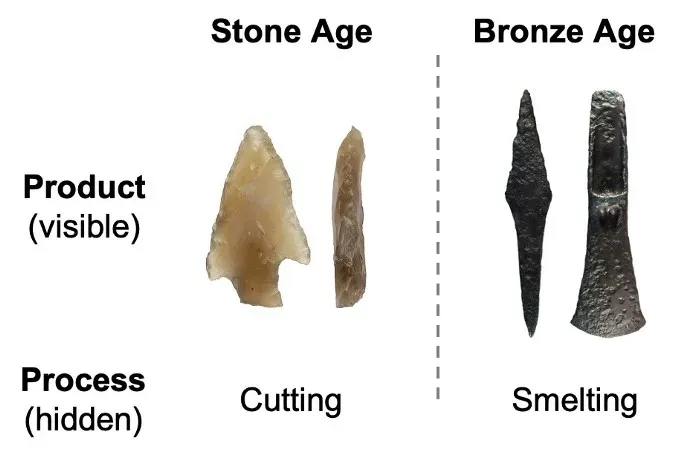

If you were asked to compare the object on the left vs the object on the right, what points would you make?

One of the first things you’d notice would be the material. The left is made of stone, the right of bronze.

You might also mention the stone arrowhead is likely not as sharp as the bronze, is probably less durable, and asymmetrical.

What you inferred but probably didn’t state explicitly would be that the manufacturing process is different too. Stone requires cutting, but bronze requires smelting.

Focusing on this topic of process, Michael Filler and Matthew Realff propose that Fundamental Manufacturing Process Innovation (FMPI) is central to progress. Let’s see what they mean by FMPI, why it’s important, and a few examples.

The authors propose that there are improvements in processes that have resulted in large visible progress for mankind. However, people overlook the changes in the intangible process, and overly focus on the changes in the physical product instead. In our arrowhead example above, people focus on the stone vs bronze outcome, without looking at the cutting vs smelting process improvement 1. These high impact process innovations are what they call FMPI.

It’s hard to notice process improvements because they’re intangible, and require you to see the situation from a different point of view. You’re abstracting away from the details, and trying to find high level relationships to represent what you’re doing. It’s somewhat like how group theory in math is trying to abstract away from practical application.

Researching FMPI is important because if you can quantify the various methods that have led to progress for humanity, you have an alternative framework of getting better. For example, knowing that assembly lines get more efficiency by factoring a process into sequential parts is helpful for seeing where else you could apply the same technique.

The practical implication on this for your daily life is to review all the recurring processes that you participate in. Whether that’s at work or at a hobby, try and see if there’s a way to rearrange the steps such that your processes are more effective:

Below, we’ll look into the different steps in process improvements, and see examples of innovations that were due to FMPI.

They define process as a connected series of steps, that transform an initial state into some other state. Re-arrangement of the steps can result in process improvement. ‘Steps’ are the building blocks of processes, and rearranging steps can get you more effective processes.

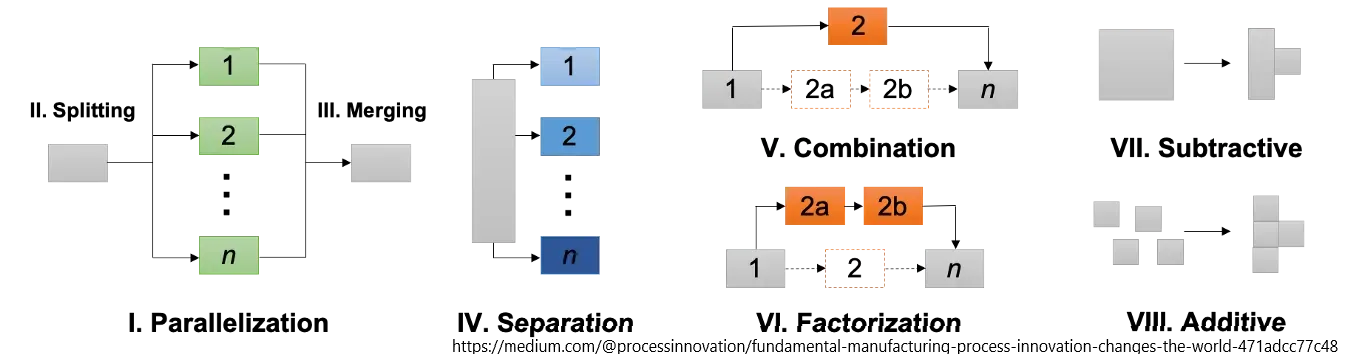

The authors propose 8 types (schemas) of process improvements:

Parallelization (type 1) refers to multiple instances of the same step being simultaneously carried out.

If you have parallelization, that implies you can split steps (type 2) and merge steps (type 3)

If you split a step and send the parts to different downstream steps, that’s known as separation (type 4)

You can combine multiple steps (type 5) or factor a step into multiple ones (type 6) 2

Lastly, you can remove things by being subtractive (type 7) or add things by being additive (type 8)

By using various variations of the 8 types above, you can change the way you do things for the better. Let’s look at more concrete examples.

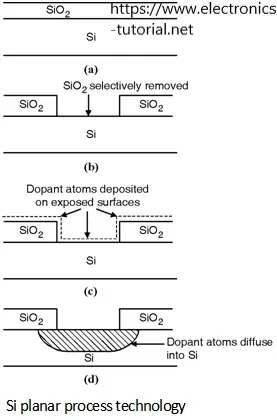

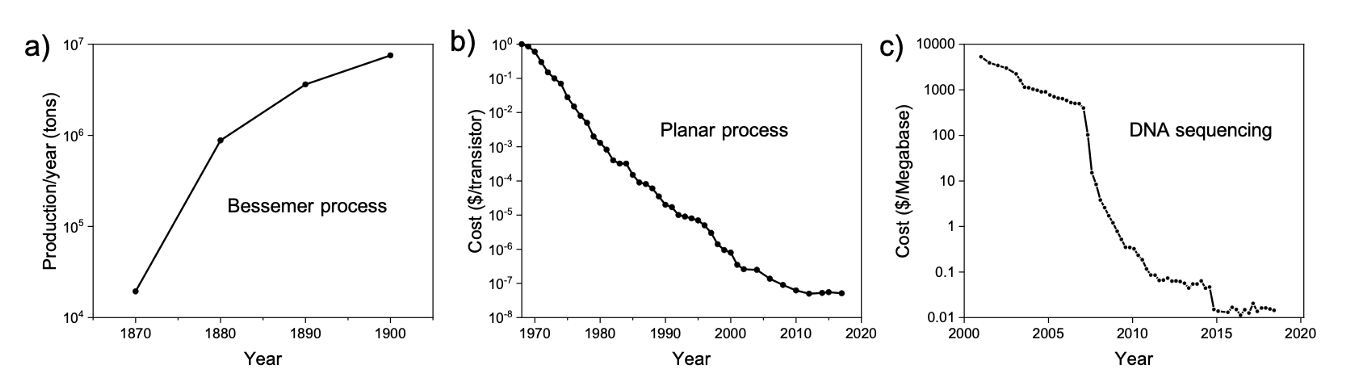

Jean Hoerni and Robert Noyce’s work at Fairchild Semiconductor in the late 1950s showed that a transistor could be made within silicon, and that circuitry could be built on top of the surface 3. Being able to have multiple transistors on a surface was an example of parallelization (type 1)

The manufacturing process also includes many subtraction (type 7) and addition (type 8) steps. In the diagram below from Electronics Tutorial, you can see the removal of silicon (SiO2) and the addition of doping material to create semiconductor properties for the material.

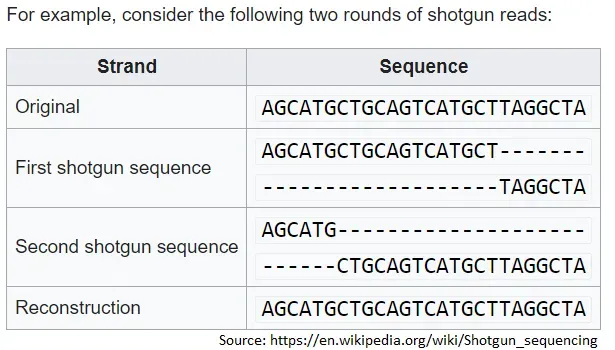

In the 1970s, DNA sequencing was slow and labour intensive, since it was thought you had to work sequentially on the entire DNA strand. Joachim Messing and Peter Seeburg developed a shotgun approach, which breaks DNA into random fragments to allow for faster sequencing. By doing multiple overlapping fragments, this allowed parallelization (type 1) in the sequencing process, greatly increasing the speed, decreasing the cost, and decreasing the amount of DNA required 4.

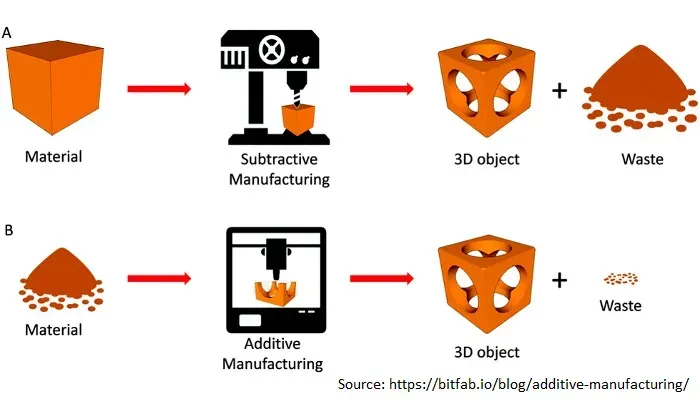

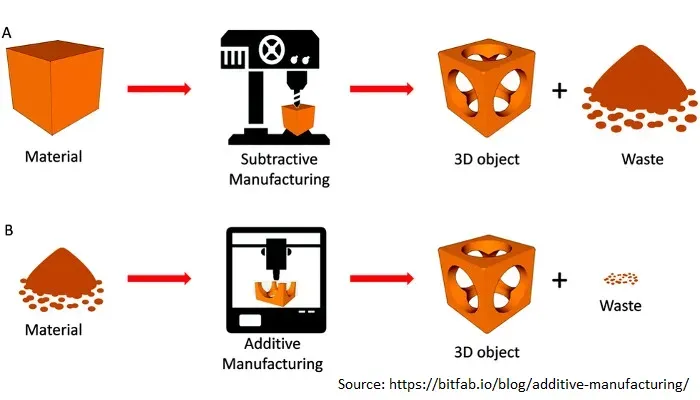

Most conventional manufacturing techniques involve subtraction (type 7) of the material from a raw form of the material. For example, if you want to create a table, you’re cutting down a tree and then sawing off the parts you don’t need.

As you can imagine, this creates wasted material. For many companies, trying to optimise the amount of intermediate product they can get from the raw product is essential for profitability. For example, fabric optimisation in the clothing industry can result in 30% cost savings 5

In contrast, 3D printing is additive (type 8). This means there’s much less waste in the production, since you’re printing nearly exactly what you need from the bottom up. Besides the cost savings, this also allows creation of more complicated structures in fewer steps.

The authors claim that the process improvements above were integral to the cost reduction in those industries as seen below.

Besides enabling a pathway for technologies to scale, FMPI has the following characteristics:

They end off with a few open questions:

They propose 3 reasons for this: a) Process has a fleeting nature, and is more transient than product b) Process improvement has a large breath of application, and is easily missed by specialised practitioners (unsure what they meant here) c) Process is thought to be just a rearrangement of steps, a trivial activity ↩

Factoring seems awfully like separation to me, and I think the difference they want to make is separation goes to different downstream steps. Factoring goes to the same step ↩

I’m not entirely sure of the specifics of semiconductor chip production, see here or this youtube video for more detail. I think the entire production process is referred to as a planar process since the silicon wafer has to be flat, and then you stack the circuitry on top of it by making the silicon oxide layer, add a photoresist layer, add a mask, expose to UV to selectively remove the mask, allowing you to etch the oxide, and then selectively dope the exposed silicon. ↩

You can find more detail in their paper here. It’s beyond what I know so not going to add more detail here. An easier to understand version of the shotgun process is here ↩

This involves using a computer (or human I suppose) to generate a fabric pattern that maximises the usage of your fabric by arranging the fabric pattern so it “covers” the material without much gaps. ↩

Get my next essays in your inbox:

Comments